‘Go to the poor,’ he said. St Vincent didn’t wait for the poor to come knocking. He was proactive in his charity.

Sometimes people don’t want to ask for help. Sometimes people can’t ask for help, even though they need it. But St Vincent circumvented that, saying you are our sister, our brother.

That spirit remains alive.

It’s Thursday, in Medellín. This is Colombia’s second largest city, built under and into the towering Andes. The breeze blowing across the mountains balances the heat into a pleasant climate. The City of Eternal Spring, they call it.

It’s a colorful place too. Street art adorns a series of buildings, plants and trees verdant in the temperate warmth.

It’s evening, and a group is trawling through the streets with shopping trollies. The street lamps guide their path. Their trollies are full of clothes and bread. There are some large silver containers too, full with aguapanela. A kind of sweet tea with a hint of lemon, it’s a staple in Colombia.

They go out every week. A few dozen of them, most in their 20s and 30s. They are happy, chatty, friendly. Even in the pouring rain. Sometimes, they take a guitar with them, making music as they go.

But they’re out on the streets because there’s suffering in Medellín too, amid the music and the color and the cool breeze. A third of Colombians live in poverty. Over half a million are homeless.

For many years Medellín was full of crack houses. Homeless people would congregate, united by a debilitating addiction to bazuko. Even pregnant women were found in them. The residents, if you can call them that, would forego a home, forego food even for their hit. Life was put on hold. The police shut down most of the crack dens. But the people still exist.

Andrés has been homeless for 11 years. 11 years of drug use, one day to the next consumed by the hit.

His is not a story of life-long poverty, though. Andres had an opportunity. He went to university, studied Law. He speaks English well, perhaps could have worked internationally. He got work as a model for a time.

But the drugs. They stopped all that opportunity, that aspiration. They didn’t so much replace the aspiration, they became it. And, like so many, forced him to the street. A grueling and precarious existence.

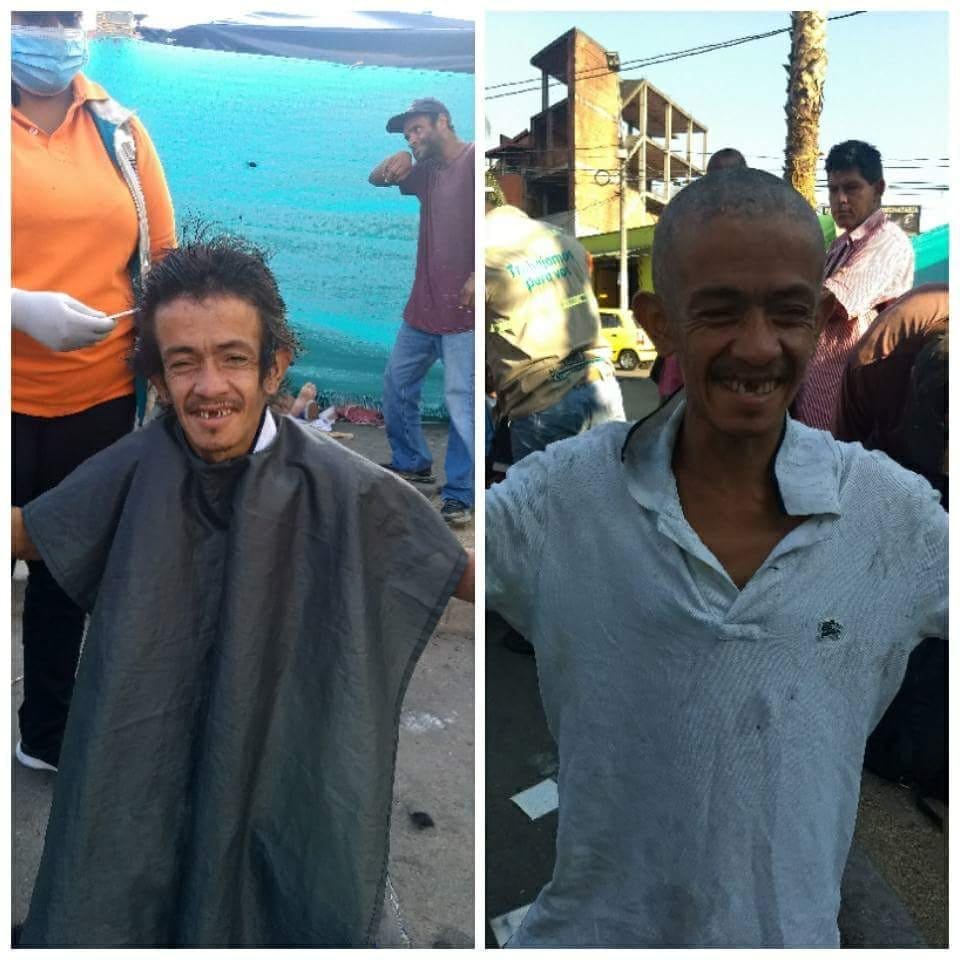

But then he was found. By the Vincentian band and their shopping trollies with clothes and bread and tea. They are the Aguapaneleros Foundation, a group of young Vincentians doing what St Vincent did all those years ago. They do this for their faith and because of it.

Dignity and visibility. That’s what this group want for the poorest, they tell me. They treat their poor brothers and sisters with dignity through their charity. But more than that, they are saying these people exist. The streets are so public and yet the people who live on them so obscured. Not in Medellín, they say. They won’t have it that way. Go to the poor.

The food and drink they offer quench thirst and hunger. But it’s so much more than that. It’s a way into someone’s life. That’s what happened with Andres, the Law graduate. The conversations, the hugs, the prayers – he feels part of a community again because he is.

Last week, some volunteers from the Foundation accompanied him to rehab. The first step, yes. The most important. A life could change. Many have because of this Foundation. Many more lives have been made just a little better with their food and their love. That’s powerful, too.

This project has been running for 20 years now, started by students and still dominated by young people. They mark it as theirs. They raise awareness about the causes of homelessness, but in their way. Regular posts on Instagram and Facebook bring these issues to the forefront. That centuries-old Vincentian spirit, public and alive – in the modern age.